Happy World Cucumber Day, everyone! Trivia Mafia co-founder Chuck here with a deep dive into the coolest gourd in the grocery aisle, as well as its curiously recurring relationship to royalty through the ages.

Like a lot of trivia enthusiasts, we here at Trivia Mafia mark the passage of time by observing nonsense holidays, many of them food-related. If you’ve ever played Trivia Mafia trivia, you probably know this — recent rounds have celebrated National Egg Day, National Hamburger Day, and National BBQ Week. Yesterday was National Fish and Chips Day, and as I write this, the country is once again celebrating National Donut Day. Another year gone.

If you’re reading this on Friday, June 14: Great news! It’s National Bourbon Day. (It’s also World Blood Donor Day, a holiday that probably shouldn’t be celebrated quite so close to National Bourbon Day.) Additionally: Happy National Cupcake Day and National Strawberry Shortcake Day to all who celebrate. And if you want to work off some of those cupcakes, shortcakes, and donuts, fear not, for the fake festivities are not exclusively culinary in flavor. Why not enjoy a stroll through a graveyard to celebrate Love Your Burial Ground Week? And while you’re at it: It’s also Meet Your Mate Week! Personally, I’ve never found true love while walking among the gravestones, but maybe I’ve been doing it wrong.

The reason I bring up all of these silly unsanctioned holidays is because June 14 is also the date set aside to celebrate the subject of today’s Friday Know-It-All: The humble cucumber. Which, as it turns out, is not so humble after all. Some trivia to prove the point: In addition to being the coolest veggie in the grocery aisle, these crunchy beauties are also great for your skin, they fight bad breath, and are even believed to cure hangovers. How cool are cucumbers? Turns out science has the answer: About 20 degrees cooler than a warm summer day. Some TikTokers think they taste like watermelon if you dip them in sugar.

(Speaking of which: Guess who has a water content even higher than the watermelon? Mother-effing cucumbers. Beating a melon at its namesake game? That’s like having better hairstyles than Harry Styles. Or being a better firefighter than this guy.)

The cuke is more than a simple vegetable.* It is, I would argue, a slice above. The divine, from the vine. A demi-gourd. Which may explain why the cucumber has a curiously recurring relationship to royalty. Which brings us to the real reason I wanted to talk about cucumbers on this World Cucumber Day: If you do even a cursory internet search for “cucumber king,” you will find… kind of a lot of cucumber kings! A weirdly copious conglomeration of crowned cukes and/or cuke-mongers. It’s a trope of history that extends back more than a millennia (way before this guy).

They say two’s a coincidence and three’s a trend, so let us now share three examples of “Cucumber Kings” through the ages.

Example 1: The Tale of Nyaung-u Sawrahan, the Cucumber King of Burma

In the 10th century CE, the plains surrounding the Irrawaddy River in what is now central Myanmar was a peaceful and fertile valley filled with farming settlements, at the center of which lay the small village of Pagan (known today as Bagan). A critical trading post along the southeastern spur of the Silk Road, Pagan grew into an important economic juncture between India and China, and soon became an immensely wealthy kingdom ruled over by a series of Buddhist monarchs. So wealthy did Pagan become that the next 200 years saw its landscape increasingly dotted with beautifully constructed — and wildly expensive — temples and pagodas, numbering more than 10,000 at Pagan’s peak in the 13th century. (Roughly one-fifth of them are still standing today.)

This is what Bagan looks like today. A thousand years ago

there were five times as many of these temples!

But before the Kingdom of Pagan became the temple-encrusted jewel of southeast Asia, it was mostly farms, and some of them grew cucumbers.

According to legend, one of those cucumber farmers was a man named Nyaung-u Sawrahan. One day, while tending his crop, Sawrahan discovered a thief among his cucumbers, snacking on his prized gourds. Sawrahan didn’t get the memo about Pagan being a peaceful farming community, so he killed the thief on the spot. Soon after, he learned that the body lying among his gourds was no mere vegetable thief — it was Theinhko, king of Pagan, who, having become separated from his hunting group, was merely seeking shelter and a meal from one of his subjects.

If the punishment for stealing a cucumber at that time was death, you can imagine the horrific fate that awaited a regicide. But Theinhko’s widow had other ideas. Fearing that her husband’s death might result in her own removal from the Pagan palace, she chose instead to marry Sawrahan — the very farmer who had murdered her husband — and recognize him as the new king. Sawrahan ruled for nearly 50 years, and was thereafter known as Taungthugyi Min, or “The Cucumber King.”

Unfortunately, while the historic record does attest to a Pagan king named Sawrahan, most experts assume this is a folk legend — another fruit from the rags-to-royalty story-vine that gave us David, “The Princess Diaries” and “King Ralph.” Cambodia even has its own version of the Cucumber King story: In that version, the king’s own gardener mistakes the king for a thief and kills him. A royal council is convened, and ultimately decides that a holy white elephant should select a successor to the throne. The elephant turned away from the slain king’s family and instead singled out the murderous gardener from the crowd. Which must have made that doomed gardener pretty happy. Or perhaps he just had a cucumber in his pocket? (Sorry.)

Example 2: Khalid Sheldrake, the Pickle King of the Uyghurs

Our next tale from the cuke-to-crown pipeline takes us all the way to the late 19th century, and to London, where a young man born Bertrand “Bertie” Sheldrake was born into a family of pickle manufacturers. Pickling was to become his life’s occupation, but not his life’s calling: That would be the spread, throughout the British Isles, of the Islamic faith, to which he was among England’s earliest converts.

Khalid Sheldrake, gherkin magnate/potential potentate.

In 1903, at age 16, Bertie Sheldrake converted to Islam, becoming one of just 300 Muslims estimated to live in England at the time. He changed his name to Khalid, and set about the task of converting as many of his fellow Britons to Islam as he could. While he wasn’t making pickles, that is.

By 1933, Sheldrake was among the most famous Muslims in the United Kingdom when he was visited by retinue from a newly formed country in far-western China known as the Islamic Republic of East Turkestan. A breakaway community of Uyghur Muslims living under the oppressive and often violent Chinese rule (a state of affairs that, sadly, continues to this day), this newly minted country was opposed by China as well as neighboring Russia, and its leaders hoped that enlisting the help of a high-profile Muslim like Sheldrake would rally support from the West to their cause. So they asked him to become their king.

Sheldrake relished the opportunity, before ultimately souring on it. News of the pickle-maker who would be king spread to all of London’s newspapers. One headline warned: “Dr. Sheldrake is heading into 57 varieties of trouble” as he and his wife convened a camel train in Beijing and began the 2,500-mile trip westward to his coronation in Kashgar. That headline proved prophetic: Before the camels arrived, the local Chinese governor had, with help from his Russian allies, crushed the Uyghur rebellion and promised death to anyone who attempted to declare themselves king of the region.

Sheldrake found himself in a bit of a… conundrum? No, that’s not the word. Anyway, he returned to England and his gherkins, to die in relative obscurity in 1947.

The flag of the short-lived First East Turkestan Republic, which one-time

British pickle baron Bertie Sheldrake nearly ruled. Oh, and PS: Happy Flag Day!

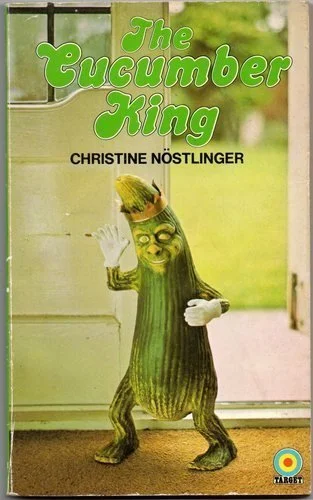

Example 3: “The Cucumber King” by Christine Nöstlinger

I’ll admit I don’t know much about this one. It’s an out-of-print Austrian children’s book from 1988 by an author I’ve never heard of, but who, upon reading her Wikipedia page, strikes me as a complete badass.

Also, its cover looks like this:

Having read a few reader reviews, it seems to be the story of an unsuspecting middle class family who, out of the blue, are visited by a cruel and authoritarian Cucumber King. He moves in and immediately assumes control over the household. Certain members of the family try to mount a revolt against the tyrant, while others (including, notably, the father) all-too-eagerly bend the knee and supplicate to their new overlord.

If anyone wants to gift me a copy of this book, I’d love to confirm my hunch that it’s both a nightmarish fever dream (as many of the best children’s books are) and an uncanny forewarning of today’s political milieu.

Was Ms. Nöstlinger’s Cucumber King inspired by the tale of the Cucumber King of Burma, or the would-be Pickle King Khalid Sheldrake? Or is there just something kingly about cucumbers? (Or queenly? Because guess what Elizabeth II ate at her own coronation.) We may never know.

And that’s all there is to know about cucumbers and their royal ilk. Happy Friday!* Yeah, I know it’s not really a vegetable. But it’s vegetable-presenting, and I subscribe to a doctrine of culinary descriptivism.