Executive VP Brenna is here this week to discuss one of her favorite authors. Happy Women’s History Month!

I first met Anne Shirley when I was about 9. She was a kindred spirit — another kid who would swing from flights of fancy to “the depths of despair” to righteous indignation (emotional regulation: it’s always been hard!). Anne was a kid who got into trouble both by accident (using liniment instead of vanilla) and on purpose (you do not have to walk the roof ridge pole just because Josie Pye dared you to!) and used long, fancy words. And, best of all for a voracious reader, she was in a series of eight books (but if you’re pressed, the first three and the very last are the best).

“Anne of Green Gables,” published in 1908 and never out of print since, is the story of an orphan adopted at age 11. Author L.M. Montgomery lost her own mother when she was not yet 2, and was raised by her maternal grandparents. They were Scottish and Irish Canadian, strict folk who shared tales of fairies and travelers. Her emotional connection to her home infused her characters (like Pat of Silver Bush); her ambition to be a writer was lifelong (like Emily of New Moon); her expansive imagination (like Anne’s) helped her navigate an isolated childhood.

Lucy Maud Montgomery — Maud to her friends, Dame after receiving the OBE in 1935 — authored 20 novels and had hundreds of short stories, poems, essays, and articles published in her lifetime. She died in 1942 (content warning for suicide), and was born in Cavendish, Prince Edward Island, in 1874, which inspired the fictional Avonlea, where her most famous character lived. Montgomery, like Anne, got her teacher’s license in Charlottetown, and taught off and on. Like Anne, she refused three proposals of marriage and went to college (Dalhousie for Montgomery, Redmond for Anne). When she did marry, at age 36, it was not a lifelong friend and future doctor like the fictional Gilbert Blythe, but a Reverend Ewen Macdonald; she later told a reporter, “Those women whom God wanted to destroy He would make into the wives of ministers.”

Montgomery was first paid for her writing at age 19. At 23, in 1898, she returned to her childhood home to support her widowed grandmother, staying until her wedding, not long after that grandmother’s death, in 1911. In those 13 years, she was making a livable income from writing, according to her extensive journals. The story of the little red-haired orphan was rejected by five publishers in 1905, so she put it in a hatbox for a time.

When “Anne of Green Gables” did come out in June 1908, it was an immediate success, with six printings before the end of the year. In 1917 began a seven-year dispute with her publisher over royalties: she’d been paid seven cents on the dollar rather than the 19 cents she was owed. The contentious case went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court (the publisher was based in Boston), she won, and was awarded $15,000 (about $372,000 currently). Montgomery is estimated to be the most successful Canadian author in sales, both during her lifetime and since, with “Anne of Green Gables” now found in 36 languages.

Montgomery wrote about her career in 1917 for a magazine series, later collected in the book “The Alpine Path,” and begins, “Was not — should not — a ‘career’ be something splendid, wonderful, spectacular at the very least, something varied and exciting? … It had never occurred to me to call [my writing] so; and so, on first thought, it did not seem to me that there was much to be said about that same long, monotonous struggle.” Turns out that work is still work even when you’re a successful writer!

For all that, Anne’s story is over 100 years old, it still feels relevant, and not just in the universal emotions of a kid wanting the latest fashion (“It would give me such a thrill, Marilla, just to wear a dress with puffed sleeves.”). Montgomery extended empathy to all the characters, each with their own distinct angles. Marilla, the aged spinster who unexpectedly loves an unasked-for little girl, is sketched sympathetically as she questions her assumptions about how to raise a good person. Before Anne goes to the teachers’ college, Anne is effusive about how much she’ll miss home, and how much she loves Marilla and Matthew. “Marilla would have given much just then to have possessed Anne’s power of putting her feelings into words; but nature and habit had willed it otherwise, and she could only put her arms close about her girl and hold her tenderly to her heart, wishing that she need never let her go.”

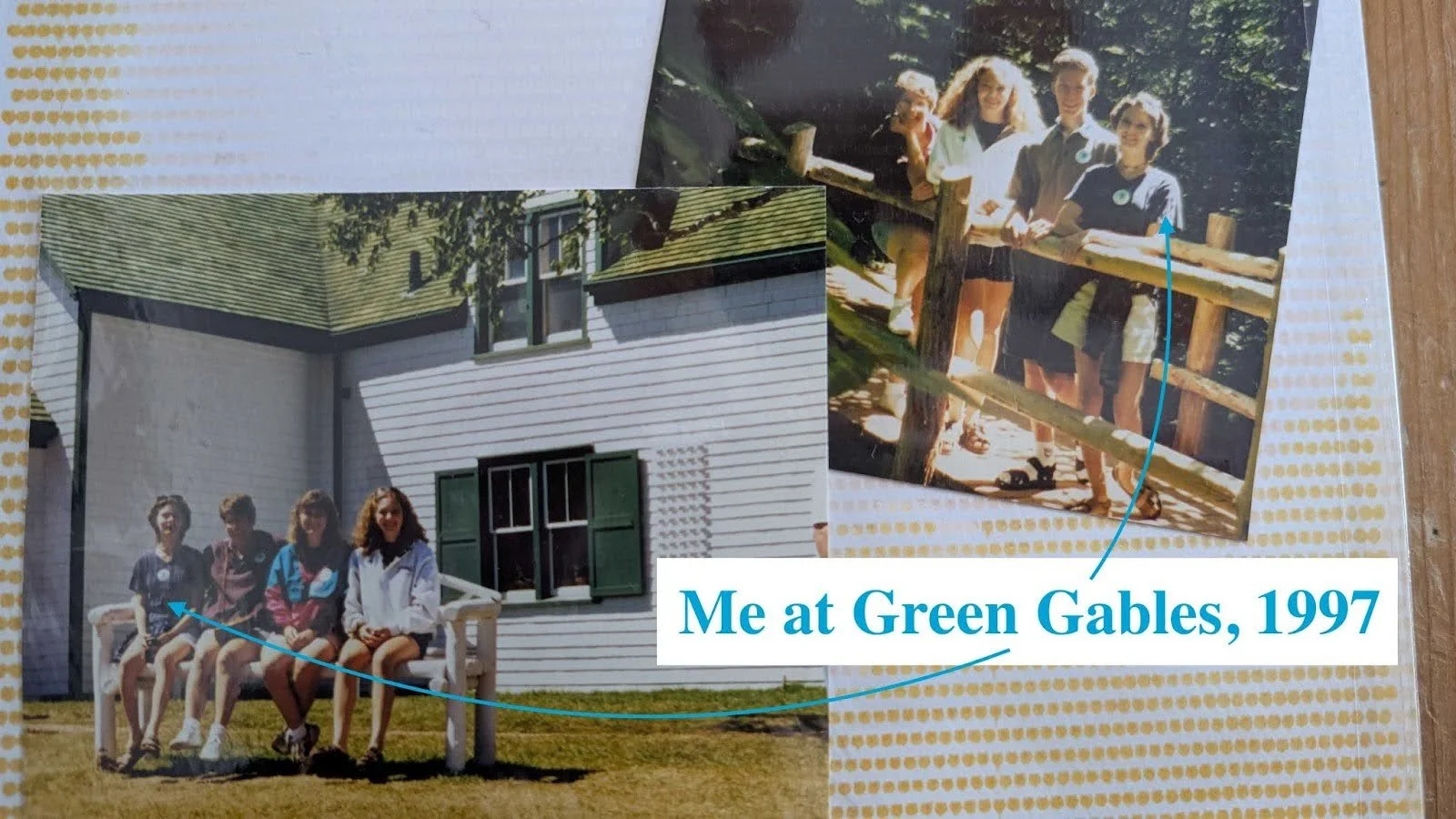

Montgomery wrote in 1901, “I don’t care for dramatized novels. They always jar on my preconceptions of the characters.” Her Anne was first adapted to film in 1919, and has since been reimagined for radio, television, anime, comics, and more than 50 times — next coming later this year in an updated Japanese version. A movie about the author herself is also in production: Megan Follows, who played Anne in what many (including me and my cousins, pictured with me at Green Gables) consider the definitive, 1985 CBC adaptation, will portray her in “Lucy. Maud.” It may not be a flawless dramatization, but as Anne would say, “isn’t it nice to think that tomorrow is a new day with no mistakes in it yet?”