Today, the Friday Know-It-All welcomes guest writer Andy Sturdevant, proprietor of a fantastic biweekly mail subscription service for fans of pen-and-paper games called Paper Palace. Each edition of Paper Palace features an entertaining dive into the rules and history of a different pen-and-paper game, as well as a short essay about Andy’s own relationship to the game and experiences playing it. This week, we’re re-running one of my personal favorite installments of Paper Palace, devoted to the playground divination game MASH. —Chuck

M-A-S-H

Background: The purpose of the game of MASH is to determine a person’s fortunes at an undetermined point in the future. Popular among grade school children for at least the past 40 years, MASH is a tool for predicting one’s life in “adulthood” — a snapshot of the subject’s material circumstances at, say, age 25 or 35 or 45. For older players, this future may be perceived as any point further out.

Number of players: Two or more; a solo version could be played with a die, deck of cards, slips of paper, or other means of selecting a small random number. However, much of the enjoyment of the games comes from the interactions with the other players after a round is completed.

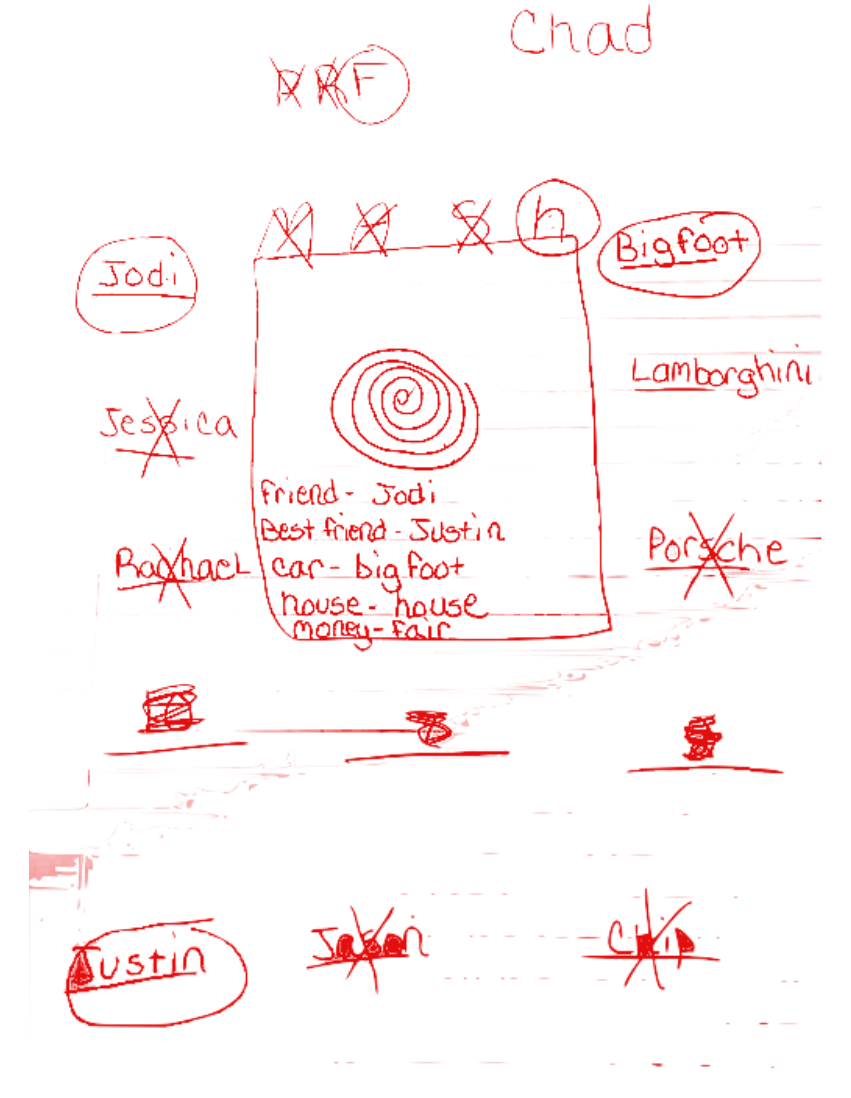

Instructions: The game begins when one player is chosen as a subject, and another as notetaker. The notetaker writes “MASH” at the top of a piece of blank paper. The subject and the other player(s), including the notetaker, contribute to writing a list of 5-10 categories. Popular categories include spouse/partner, occupation, spouse/partner’s occupation, number of children, make and model of car, car color, place of residence, annual income, and, most importantly, type of home lived in, which gives the game’s title its acronym: “mansion / apartment / shack / house.” (The “s” can also stand for “streets” or “shed,” or “sewer” or “swamp” if the other players are not committed to strict realism.) Each player contributes suggestions to each category for a total of 4-6 selections. Ideally, there should be 2-3 choices regarded by the group as positive outcomes (for example, “good” cars in 1990 might have included a Ferrari F50, a Lamborghini Diablo, or a Chevrolet Corvette), and the remainder a list of negative outcomes (a Yugo GV, an AMC Gremlin, and an unspecified “jalopy,” for example – or, god help you, no car at all). One or two options may be perceived as neutral outcomes (a 1988 model year Honda Accord or Jeep Cherokee). Ultimately, the notetaker is the arbiter of what is or isn’t included for each round.

The notetaker then draws a spiral on the page emanating outward, out of view of the subject. They may draw slowly, or quickly, or alternate. The subject calls “stop” after several seconds, and the notetaker then draws a line from the center of the spiral to the endpoint. The notetaker counts the number of times the line has intercepted the spiral. This is the number used to count off the options.

The notetaker then counts each item down the page (including the four letters in the MASH title), and crosses off the answer that they land on. For instance, if three lines were counted in the swirl, every third answer is crossed off the list. Each letter in MASH is considered an answer and should be crossed off accordingly; in the case of a three, the notetaker will cross off the “S” in “MASH,” then the second option in the first category, and so forth. This continues until there is only one item remaining in each category. Each selection is circled, and the group discusses the results. For additional rounds, participants trade off the notetaker and subject roles.

Variations: On the sample MASH game on the following page, the notetaker has chosen to count off in each individual category until there’s an answer (first MASH, then car, then best friend, etc.), as opposed to every option across all categories.

It was most likely Imran who introduced me to MASH.

This would have been sometime in 1989 or 1990, at Wilder Elementary in Louisville, Kentucky, probably during lunchtime, or recess, or one of those aimless, unstructured days at the end of the school year. I am still in touch with Imran, so I texted him while writing this, and he confirms we played it regularly. He suspects it was Rhonda D. who introduced MASH to our friend group. I looked Rhonda up on LinkedIn, found she was living on the East Coast, and messaged her to find out if she could recall where she learned it. She thought it was from her friend Erica, who had an older sister well-versed in interactive childhood games of divination. Rhonda lost touch with Erica after middle school, and Erica’s last name was common enough that I didn’t manage to find her or her sister — though even if I had, how far back could I possibly follow the trail?

It’s possible that children have been playing MASH or something like it since the 19th century, though I doubt they’d have called it MASH — that name situates it very definitely in the 1970s and early 1980s, for reasons that may already be clear to you, and which I will go into later. Something about these folkloric games make us want to believe they’re as old as civilization. Some of them are: Variations on Tic-Tac-Toe date to 1300 BCE.

Surprisingly (or not?) there isn’t a large corpus of research out there on MASH. The Wikipedia page (which itself is tagged “low-importance board and table game articles”) lists only two sources, one of which is a WikiHow article, which in turn is sourced entirely from a YouTube video from last year. That YouTube video, from an ’80s nostalgia channel, is sourced entirely from the creator’s memory. Personal memory is obviously the foundation of all folklore, but at some point, it becomes valuable to fix those personal memories to larger socio-historical structures and to determine their origins as best as we can. That’s why Paper Palace exists, after all; I think “low-importance board and table game researcher” was one of my MASH jobs from a game in fifth grade, alongside, I am sure, “President,” “motorcycle stunt man,” and “fart-smeller.” Let it never be said that MASH dreams don’t come true.

First, the name. It’s suggested on the Wikipedia page that there’s a connection between the name MASH and “mash,” a term for a crush that dates to the 1880s – it lives on in the term “mash note.” The linguistic connection between the two seems more dubious to me, though, since MASH is less a game of romantic fulfillment than material fulfillment. This is why the title of the game refers to types of buildings, and not the identity of your mash. Would a game of MASH ending in a happy home life, with marriage to your true love and several healthy, happy children, but living in a shack, working as a janitor, and driving a decaying Model T be considered a positive outcome? In the circles I was playing in, circa the late 1980s: No, not really. Kids have a much less romantic view of life than young adults. What use is true love if you’re literally living in a swamp? (Of course, this was also Reagan/Bush-era suburbia, which could have also been just a more cravenly materialistic milieu.) The opposite, on the other hand, living in a mansion, driving a BMW and working as a marine biologist with your own TV show, though married to an intensely disliked teacher? Net positive, probably. I can see Imran shrugging and saying, “Hey, married to [unpopular music teacher] Ms. Stegenga, that’s a bummer, but at least you’ve got the Beemer and the TV show.”

There are a few factors that make me think that, like “Sesame Street” or “Free to Be You and Me,” MASH is an innovation in children’s entertainment of the last half of the 20th century. Casual references to it in subreddits and Internet forums suggest it was being played in the early 1980s, and possibly before. Melissa Joan Hart (b. 1976, Long Island) and Lisa Brennan-Jobs (b. 1978, Portland, Oregon) both mention playing it in elementary and middle school in their memoirs. As noted, I recall playing it fairly often in the late 1980s, even though it was perceived as a “girl’s game.”

Memory is hazy, though. I wanted some contemporary sources. The very earliest print reference to MASH I managed to find is only from 1988. It’s in a thesis paper by an Indiana University graduate student named Mary Susan Koske, titled “Finnish and American Adolescent Fantasy and Humor: An Analysis of Personal and Social Folklore in Educational Contexts.” Koske studied personal folklore, or “solitary communication”: daydreams, self-myths and fantasies among adolescents. These include social games that might serve as mediums for expressing those daydreams and fantasies. Koske did field research in Helsinki, Finland and southern Indiana, conducting extensive interviews with high school freshmen throughout the 1985-86 school year. Subjects in both Finland and the U.S. played an almost identical version of MASH, though only in America was it called by that name. (Sadly, she doesn’t mention what the Finnish variant was called.) MASH’s presence on both sides of the Atlantic suggests that by the mid-1980s, it had been around long enough to be present in the imaginative life of kids across the Western world.

Koske connected the game to the “shopping list” approach to heteronormative adulthood wish fulfillment in personal daydreams from American students. Here is one Indiana girl Koske interviews describing her vision of her future, which has a MASH-like quality in the specifics (job, housing, children, salary):

“I’d like to become an archaeologist because I’d like to know why people did what they did. I don’t want to get married until I’ve got my career underway. Which would probably be in about 8-10 years. Which means I’d be around 24-26 years old. I’d like to live in Chicago or New York, but I would also enjoy living in the country. If I lived in a city I’d like to live in a house like the house in ‘The Cosby Show.’ If I live in the country I’d like to live in a big old house. I’d like to have 1 or 2 kids, have about 2 dogs and maybe 1 cat. If I become an archaeologist I’d probably travel to a lot of places, but I would also like to travel around the world. With my leisure time I’d like to spend it with my husband on a vacation and some-times with my children, too! I’d like to stay in the Midwest and East Coast regions. Because I don’t think I could live without snow... I’d like to make a lot of money, but I don’t want to be rich. I’d like to be well-off. Between middle-class and upper-class. I want to have a big kitchen so I can cook. I love to bake cakes and other things.”

All of which could have been positive outcomes in a game of MASH. From my own experiences, I don’t recall how seriously I took MASH as a tool for parsing future career and romantic prospects. Not very, I think. I remember it being mostly a joke, but as Koske points out in her paper, the joking is the point. MASH and games like it are really about having an opportunity to talk about your desires in an informal but structured environment. “When girls play this game,” Koske writes, “they reveal their opinions about the boys mentioned. Ordinarily, girls try to mask real feelings for boys they may like, on whom they have ‘crushes’ or about whom they have privately fantasized. However, games of divination provide a context in which actual feelings and desires are expressed.” If the subject has a specific boy eliminated from the marriage category, for example, “she may share her relief or disappointment with the other girls, depending on the boy named.”

MASH stuck with kids of this generation as they aged into adulthood — and, presumably, into mansions, apartments, shacks and houses of their own. The earliest reference in the mainstream press I can find is backward-gazing, from an article in The Daily Illini in 2000, written by Michael Piwoni, a theater student at the University of Illinois. “When summer comes to Champaign-Urbana, boredom sets in,” he writes. He suggests MASH as a nostalgic pastime for bored Y2K-era college students trying to kill time at their stupid summer office jobs.

In terms of identifying a general birth date for MASH as we know it, all of these fac- tors indicate to me that it’s a phenomenon of the late Gen-X/early millennial period.

Of course, MASH didn’t just spring fully formed into childhood consciousness on January 1, 1975. There is a history of “fortune-telling” parlor games using pencils and paper and mostly related to future marriage prospects that probably served as antecedents. A book of parlor games from 1917 describes one such game called Little Fortune Teller that uses an 11x11 grid and a random stroke of a pencil, and is so complex it requires a table several pages long of potential outcomes: “many lovers, but die single,” “you will see your intended next Sunday for the first time,” etc. Even more byzantine is one called Fateful Questions, which utilizes a 9x63 grid (!!), involves some light mathematical formulas, and has 20 pages of tables outlining potential outcomes to questions from “will my family approve my marriage?” to “what shall be the chief fault of my husband/wife?”

The genius of MASH was in taking the same principles — your romantic future determined by random pen strokes — and simplifying it. MASH is simple enough that grade-school kids can grasp the general principle, and varied enough that an imaginative group of those same kids can cook up all kinds of scenarios much weirder and darker than “Will my family approve my marriage?” If you end up married to Axl Rose living in a volcano in France with 10 kids to support on a demolition derby driver’s salary, it’s hard to imagine the more priggish members of your family would be pleased with your life decisions. This ability to queer the outcomes to the limits of your own imagination makes me wonder if it’s still played by young people with a more fluid sense of gender roles. MASH could easily be adapted for this sensibility. Whether it is or not in 2023 wasn’t clear from the cursory inquiries I made to friends with school-aged kids.

Ultimately it’s the name which definitely situates it in a late ’70s/early ’80s context. It may be impossible to know for certain if there’s a connection between MASH the game and “M*A*S*H” the long-running Korean War TV comedy, but I have to think there is. Koske thinks so, too, claiming the name is directly inspired by the show, which I presume was reported to her by her interview subjects. What does predicting your future have to do with a tragicomic prime time TV show about the Korean War? Not much, on the surface, but for those readers born after 1985, I will posit this: You can’t understand what a monumental presence “M*A*S*H” was in the cultural imagination of the United States between 1972 and 1983. I came of TV-watching age a few years removed, and even then, it seemed like it was on six times a day.

So this may be the connection. I think it was film critic Amy Nicholson who wrote that hearing the opening credits to “M*A*S*H” was like an audio warning to ’80s kids that cartoon time was over, boring adult time was commencing, and you should go to bed. MASH, for all the glamor of potentially living in a mansion and driving a Corvette, is nothing if not a harbinger of boring adult times to come — economic stress, complicated relationships, substandard housing, crappy cars, professional disappointment. For all of its fantasy, MASH suggests the onslaught of adulthood as sure as those opening acoustic guitar notes of “Suicide Is Painless” and the sounds of those Huey helicopters flying in over the mountains.

Andy Sturdevant (he/him) is a writer, artist, and designer. He has also created art installations, publications, performances and public events, sometimes all coexisting in one project. He was born in Columbus, Ohio, raised in Louisville, Kentucky and has lived in Minneapolis, Minnesota since 2005.