Editor Chuck here today to address our past mistakes.

This is a story about being wrong.

It's not a comfortable topic for me, a trivia writer penning a newsletter that claims to "Know It All." Seeing as how Trivia Mafia is in the business of rewarding people for being right about stuff, we hold ourselves to a pretty high standard when it comes to the whole "not being wrong" thing.

But that framework gives being wrong a bad name, and over the years, I've come to love being wrong. In the trivia business, we necessarily trade in the binary of right and wrong—there's no room for ambiguity in a trivia question—and all of the currency is on the "right" side of that ledger. This puts a premium on certainty (this isn't "The Friday Maybe-Knows-It-All-But-Then-Again-Maybe-Not," after all). Among lovers of trivia, certainty is a curse. Curiosity should be the coin of the realm. Curiosity opens doors that certainty ignores. Certainty is the enemy of curiosity. I think it is, anyway.

And that's why I love finding out when I'm wrong about something. Lucky for me, our trivia players and newsletter readers are more than happy to us know when Trivia Mafia gets something wrong, or at least not fully correct. That's what happened yesterday, after we asked the following question:

"In 1870, a nutritional study of a particular vegetable misstated its iron content as being 10 times the real number. This led to a misperception about the health benefits of this vegetable that persists to this day. Name that vegetable!"

The answer we were looking for was "spinach." This is a classic trivia question. It's based on a long-told story that the cartoon character Popeye's affinity for spinach was based on a typo that misplaced a decimal point in a 19th-century study about the vegetable's iron content. Furthermore, because the tumescently forearmed Sailor-Man did such a fine job selling spinach as a performance-enhancing miracle food, the green crop's sales reportedly surged 33 percent, despite its overhyped health benefits. And during the Dust Bowl era no less, when most other agribusiness in the U.S. was withering on the vine. It's a fun little parable that's been retold thousands of times by data researchers, copy editors, and humble trivia-mongers. The moral: Check your facts. Typos have consequences.

"Morning Rounds" Reader Jon had clearly heard this story when he emailed us this small but ultimately shattering note: "Because I couldn't remember whether the spinach iron content was a myth, or a myth of a myth, I did a little digging."

What he dug up, and what I found buried even further below that, was this: The story of Popeye, spinach, and the misplaced decimal isn’t just a myth of a myth. It goes deeper than that. It's myths all the way down.

***

What reader Jon shared with us is a white paper by British researcher Mike Sutton from 2010, titled "Spinach, Iron, and Popeye: Ironic lessons from biochemistry and history on the importance of healthy eating, healthy skepticism and adequate citation." For a research paper, it's an awfully entertaining read. But it's still a research paper, and it's a long trip down a deep rabbit hole, so I'll try to summarize:

There really were studies that showed 10x discrepancies in the iron content in spinach. But these were done in the 1930s, and Dr. Sutton found no evidence that they were the result of a decimal point error. More likely, they were the result of non-uniform testing techniques. Some researched studies fresh spinach, while others studied dried spinach, the mineral content of which is more concentrated.

Around this same time, there was a University of Wisconsin study that concluded only around 25 percent of the iron in spinach is absorbable by the human body. This is due to the presence in spinach of oxalic acid in spinach, which binds with iron and reduces its absorption. [Ed. note: This is also why spinach makes your teeth feel fuzzy. - Ruby] This finding led to numerous newspapers articles in 1934 claiming that, despite what Popeye might tell you, spinach may not be as good for you as previously thought.

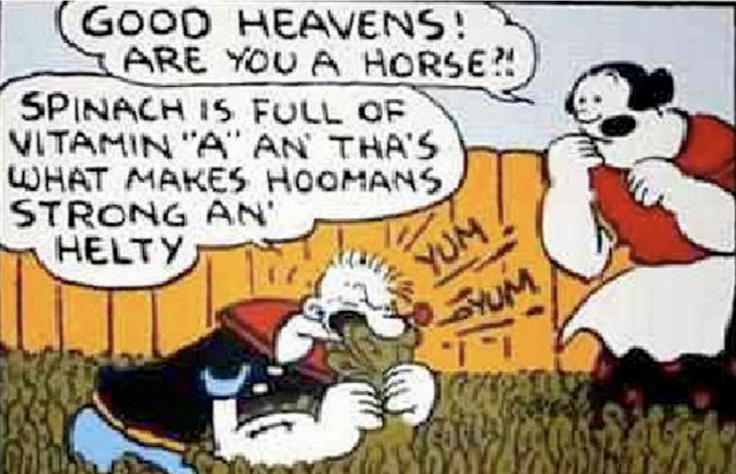

This was the first time Popeye was linked specifically to the iron content in spinach. Because here's the real kicker: After surveying the full archive of Popeye cartoons, Dr. Sutton found that the cartoon sailor never even mentions iron as a reason to eat spinach. In fact, in one panel from 1932, Popeye specifically says "Spinach is full of vitamin A, an' that's what makes hoomans strong an' helty." In other words: All this claptrap about iron has been beside the point this whole time. It was vitamin A all along! (Nevermind that vitamin A is known to strengthen only eyesight, its effects on tattooed forearms being, far as I can tell, negligible.)

So where did this story about the misplaced decimal come from? Dr. Sutton claimed in his paper that it was probably the invention of a British scientist named T.J. Hamblin, who in 1981 was assigned to write a humorous article for the Christmas edition of the British Medical Journal. The resulting article, titled "Fake!", contained this line: "German chemists reinvestigating the iron content of spinach had shown in the 1930s that the original workers had put the decimal point in the wrong place and made a tenfold overestimate of its value. Spinach is no better for you than cabbage, Brussels sprouts, or broccoli. For a source of iron Popeye would have been better off chewing the cans." When Sutton asked Hamblin for his source for this story, Hamblin couldn't remember where he'd seen it, only mentioning that he thought it might have been in an issue of Reader's Digest. No such mention of spinach, iron, or Popeye has ever been found in the Reader’s Digest archive. Dr. Sutton’s conclusion: Hamblin probably just made it up.

Finally: While spinach isn't as full of iron as previously believed, it's still just as high in iron as many other leafy green vegetables. In other words: Pretty darn high in iron. (Especially if you cook or boil it, which breaks down the oxalic acid.) In fact, it contains more iron than red meat.

All of which means: The story of Popeye eating spinach due to a long-forgotten 19th-century typo overstating the iron content in spinach is, almost certainly, false. The delicious (and, perhaps, nutritious?) irony: This very story has been told countless time as a warning about the pitfalls of not fully checking your facts.

Great story, right? A 90-year-old story about the importance of fact checking is itself fact checked and found false. And all is right again. Right?

If you read the first sentence of this piece, you probably know what happens next. Dr. Sutton? The researcher who took us down that rabbit hole and came out so certain that everyone in this story had gotten everything wrong?

He was wrong too.

***

Four years after publishing "Spinach, Iron, and Popeye," Dr. Sutton published an update, burrowing further down this leporid labyrinth. In this paper, titled "The Spinach, Popeye, Iron, Decimal Error Myth is Finally Busted," he reveals that T.J. Hamblin did not, in fact, make up the mistaken-decimal story, as he'd previously written. It turns out, he was simply quoting another British nutritionist, one Arnold Bender, who had given a speech in 1972 in which he retold the Popeye story, complete with the decimal point detail. Bender then repeated the story in a letter to The Spectator in 1977: "In 1937 Professor Schupan eventually repeated the analysis of spinach and found that it contained no more iron than did any other leafy vegetable, only one-tenth of the amount previously reported. The fame of spinach appears to have been based on a misplaced decimal point."

At last, we have a source for the decimal story! But who is this Professor Schupan? Dr. Sutton can't find any writing from anyone with that name from 1937. But he reads into Bender's phrasing—"The fame of spinach appears to have been based..."—enough evidence to settle the case that no such decimal typo ever actually occurred. Myth busted.

Unfortunately (are you noticing a trend here?), the good Dr. Sutton was wrong about this as well. Because there actually was a decimal point error.

It just wasn't in a study about spinach.

Allow me at this point to introduce you to one Joachim "JL" Dagg, a schoolteacher from Germany whose blog, Weltmurksbude (Google tells me it means “world garbage site”) contains by far the most comprehensive overview and thorough untangling of the Spinach/Iron/Popeye kerfuffle I've yet to find. Again, his posts are very long, and they are many, so I will now attempt to summarize his findings in a way that doesn't drag this already-to-long article on for too much longer. Here’s what Dagg has found:

There was indeed a Professor Schupan. But Bender got his name wrong: It's actually Werner Schuphan (note the extra “h”). He was a German researcher from the 1930s whose study focussed on the nutritional content of various vegetables, including spinach.

Professor Schuphan did not publish anything in 1937 about the iron content in spinach.

He did, however, publish about the vitamin A content in spinach, making him a strong candidate for being the very person responsible for Popeye creator Elzie Segar choosing spinach as his character's favorite vegetable in the first place.

Later that decade (in 1939), a group of researchers studying iron content in a variety of vegetables and legumes published a study that misstated the iron found in butter beans by 10x. From a 1940 edition of the Journal of Home Economics: “The iron content in mg. per gm. of six samples of peas and beans.... varied from 0.053 for green split peas and yellow peas to 0.087 for black-eyed peas. Because of a typographical error in the decimal point, the value for the butter beans as given is ten times too high."

The likeliest conclusion of all this: In the 1970s, Arnold Bender recalled that there had been studies conducted 40 years earlier that found spinach had less iron (or less absorbable iron) than previously believed. He also recalled a study that misstated iron content by a factor of 10. He failed to realize that this study was actually about beans, and ultimately conflated these two memories in a speech in 1972. This later inspired T.J. Hamblin to repeat the decimal myth in a humorous 1981 article. This eventually eventually found fertile ground on internet message boards later that decade, and it has flourished online ever since.

There really was a recording error in a lab study about the iron content in certain vegetables. And there really was a cartoon character whose affinity for spinach created a sales boom in the middle of the Great Depression. But these two facts have nothing to do with one another.

Although… who knows? Maybe this is wrong too.

If there's a through-line anywhere to be found in this can of worms (side note: also high in iron), it's that everyone involved has been a little bit wrong about almost everything. But all these wrongs have slowly circled the truth, and that, in the end, is the whole point. Science is the process of being a little less wrong over and over and over again, until finally you're not. In the 1870s, some scientists studied the iron content of spinach. They got it a little wrong. In the 1930s, some more scientists tried again, and figured some more stuff out, but got other stuff wrong. In 2023, you and I learned more than we ever thought it was possible to know about the iron content of spinach. Which, all things considered, is pretty high. Turns out Popeye was right all along.

My takeaway: The guy who says "I yam what I yam" should've just eaten yams. They're also packed with vitamin A. Pretty high in iron, too.